Our curate Marion is on the chaplaincy team at a nearby prison. The festivals of a variety of religious traditions are celebrated there, and the custom is that every now and again the prison kitchen prepares a particular foodstuff related to that festival. Just before Christmas it was the pagans' turn, so for Yule they made a huge chocolate Yule log decorated with sugar-paste mushrooms (because that's what the Druids would have had). Marion and the Baptist chaplain sat in the chapel and a grand total of 0 pagans turned up. After a while the silence became palpable.

Baptist minister: It would be wrong to waste this, wouldn't it?

And so they cut the Yule log up and had a bit each.

Marion: I don't suppose this counts as 'food sacrificed to idols' which St Paul says Christians aren't supposed to eat, does it?

Silence.

Baptist minister: Nooo, it can't do.

Thursday, 31 January 2019

Tuesday, 29 January 2019

Shifting Sands

It's been a while since I last posted about the Queen of Dorset. Her latest

project has been scoring the new production of All About Eve, starting

imminently at the Noel Coward Theatre in central London. The director, Ivo van

Hove, told What’s On Stage

when we started talking I felt she immediately connected

with the characters. She is at a point in her life when she wants to go to

another level, to the next step, and that is also what Margo – Gillian

Anderson's character – is struggling with

This is more than she would ever say herself. Now, careful Pollywatchers

have noticed suggestive things happening in the singer’s circumstances over the

last few months. First, she sold the flat in Los Angeles (the 'holiday cottage') which she’s had since

2003. Then the private company established in 1998 to hold her income from touring was wound up. These moves released about £3.5M, not a colossal

fortune but a significant amount of money: it may be that she plans to do something

definite with it, or that she’s just disposing of parts of her life that aren’t

relevant any more. Finally PJH’s agents revealed that she’d given them her old

piano, which now adorns their London offices - not in itself an earth-shattering

step but adding to a picture of transition. Something is happening, anyway.

The singer’s last great volte-face was in the mid-2000s when she

hit that liminal age, 35, junked her existing musical style, started wearing

virtually nothing but black or white (mostly the former), and began talking in a significantly

different way about her work, pushing herself into the background. I’ve always

thought the death of her grandmother had something to do with this. Now she

approaches 50 and I suspect that the composition and delivery of The Hope Six

Demolition Project has had a similar galvanising effect. The only public statement she’s ever

made about the making of the album was that she found converting the poems she’d

composed during her foreign trips with Seamus Murphy into songs much harder than

she thought she would. For such a self-critical person this would on its own be

enough to provoke a bit of introspection, but remember what else happened. During

the research and planning stage, she deliberately exposed herself to human need

and suffering and confronted her own inability to help. Then, when Hope Six

emerged, she found herself criticised, not just musically (which she’s used

to ignoring) but personally and politically, and not only by mayors and

councillors but by people on the ground, from the very communities she aimed to

speak for. She managed to effect a reconciliation with the good souls of the Union

Temple Baptist Church in Anacostia, but that would have been another new and

bruising experience. Perhaps when the long-awaited documentary about the Hope Six project finally emerges

later in the year we may learn more. Perhaps!

You can quite understand some soul-searching might result

from all that. I doubt it will involve giving up music, though she’s decided to

do that in the past and had to be dissuaded by the closest of friends. Her

sense of vocation is strong, though that can change (even the prophets often

only prophesied for a time), and your understanding of what your vocation

means can shift over the years, and send you searching somewhere else. We wait

to see what emerges from Dorset next.

On its own, the age of 50 means no more than any other, but

it has the psychological significance of being halfway to a century, and for

modern western people I suppose it opens the second half of middle-age whereas

35 opens the first. My birthday will only be a few weeks behind Polly’s this

Autumn (strange how that happens so often!) and so I face the same milestone.

A couple of weeks ago the bishop asked me to take on a

position of wider responsibility in the diocese, a request which horrified me. I

concluded that I was right to be horrified, that I wasn’t up to it and asked

that the cup should pass from me. The bishop acceded and no more has been said

of it. But if I am not to do that, what should I do? For the last few months

people I meet around the diocese have been asking me ‘How long have you been at

Swanvale Halt now?’ and come September the answer will be ten years, another

essentially meaningless but thought-provoking moment. I asked the Archdeacon

whether there’s someone I could talk through my ministry with and he has put me

in touch with retired Bishop Colin. I don’t necessarily think any conversation

will result in me concluding I should move on from here, but there must be

change – because there must always be. ‘Here on earth,’ said Cardinal Newman, ‘to

be human is to change and to be perfect is to have changed often.’ PJH is an

example to me in her restless commitment to transformation, as in much else.

Sunday, 27 January 2019

Escaping the Void

Years ago in Goremead I met Hari and Peter. They didn't worship at Goremead Church but had been members of a tiny independent chapel at the far side of the village. Peter had been a teacher and missionary many years before, but had lost his faith and by the time I met him had the beginnings of dementia. I had a couple of conversations with him about what Jesus had actually been on about. 'I don't believe in him any more,' said Peter, 'but I just can't forget about this man. I still love him.' His eyes glistened. Peter recovered his faith a few weeks before he died, and how much this must have been a relief to him and probably those around him too became clear from a volume of poetry Hari sent me after Christmas, compiled from Peter's papers after his death. I began reading them as a break in the middle of the Collected Poems of George Mackay Brown, whose relentless Orkney-ness does wear one down after 250 pages. But Peter's verse is not light relief. In fact it makes Thomas Hardy read like Spike Milligan. Meaninglessness and existential angst sprawl over every page: the Void doesn't so much stare back from the book as leap out and shake you round the neck.

On the train taking me towards my meeting with S.D. last week I found myself trying to answer the question I encourage every Christian to try to answer for themselves, that is, What is it Jesus has done for you? There are general theological answers to this involving sin and redemption, but they didn't play a great role in my conversion, shockingly. If I'm honest, I can't say my sense of the cussedness and wrongness of things, the dark fault line that runs through all our human endeavours and so often turns them to the bad, formed a problem over which I fretted and to which God was 'the answer'. In fact, what Jesus rescued me from, if anything, was the horror of meaninglessness, and reassured me that I and everything around me mattered, on a cosmic level.

I knew about that, but sitting waiting for my connection at Clapham Junction revealed something else. I often say that without Christ we would not know what love truly is, but I hadn't seen the connection between this theme and the existential one. There was a time (very occasionally there still is) when I would look around at my fellow human beings and see what Dr Bones would once have called a parade of meat-puppets, busy microbes doomed to die and striving to ignore the fact. A lot of Peter's poems were about that. But if there was a God, and meaning, and love was possible, and he loved me, then he loved all these silly beings too despite their frailty, frail and silly in ways not much different from the ways in which I am frail and silly. And that meant I couldn't regard them so negatively any more. Jesus not only gave me an example of love, not only taught me what love is, but even made it possible. He made it possible for me to sit at a busy railway station and smile, and dance inside for joy. He not only rescued me from meaninglessness, he rescued me from contempt.

God knows how I explain that to anyone, though.

On the train taking me towards my meeting with S.D. last week I found myself trying to answer the question I encourage every Christian to try to answer for themselves, that is, What is it Jesus has done for you? There are general theological answers to this involving sin and redemption, but they didn't play a great role in my conversion, shockingly. If I'm honest, I can't say my sense of the cussedness and wrongness of things, the dark fault line that runs through all our human endeavours and so often turns them to the bad, formed a problem over which I fretted and to which God was 'the answer'. In fact, what Jesus rescued me from, if anything, was the horror of meaninglessness, and reassured me that I and everything around me mattered, on a cosmic level.

I knew about that, but sitting waiting for my connection at Clapham Junction revealed something else. I often say that without Christ we would not know what love truly is, but I hadn't seen the connection between this theme and the existential one. There was a time (very occasionally there still is) when I would look around at my fellow human beings and see what Dr Bones would once have called a parade of meat-puppets, busy microbes doomed to die and striving to ignore the fact. A lot of Peter's poems were about that. But if there was a God, and meaning, and love was possible, and he loved me, then he loved all these silly beings too despite their frailty, frail and silly in ways not much different from the ways in which I am frail and silly. And that meant I couldn't regard them so negatively any more. Jesus not only gave me an example of love, not only taught me what love is, but even made it possible. He made it possible for me to sit at a busy railway station and smile, and dance inside for joy. He not only rescued me from meaninglessness, he rescued me from contempt.

God knows how I explain that to anyone, though.

Labels:

atheism,

evangelism,

laity,

poetry,

spiritual life

Friday, 25 January 2019

Woking Two

A second trip to look at the churches of Woking brought me,

first, to St Peter’s Old Woking. The mother-church of the town itself, St

Peter’s now joins in the general Evangelical flavour of Woking Anglicanism

despite its picturesque elements dating back to earlier stages in its life. It

seems to be another church battered about by a Victorian restoration which

brought in decorated floor tiles and windows depicting saints but got no

further than that liturgically. The chancel was refurbished quite late in a sort of pseudo-Jacobean style, in

memory of an incumbent who died in 1911. I need to ask about some odd metal

diamonds laid into the dais where I presume they wheel in an altar when

required. Surely they don’t use the old high altar at the east end? - and were it me I would have to align it properly against the middle of the wall ...

My chum the vicar of St Andrew’s Goldsworth Park said it

wouldn’t delay me very long, and it didn’t. This building dates to the 1980s

and it’s worth comparing it with St Barnabas, Iford, a 1960s church of which I

am very fond and which shares a similar plan, church upstairs and ancillary

rooms below: at Iford, however, a general Catholic ethos means the fittings

are massively and immovably built of concrete whereas at Goldsworth Park they

don’t even have a fixed font – one gets brought in from a cupboard when needed.

The baptismal pool is under the carpet of the café downstairs! Kate the vicar

(no point not using her real name) recounted how St John’s is setting up a Woking

network of ‘Gospel Churches’ which ‘Open Evangelical’ St Andrew’s definitely

hasn’t been asked to join.

My chum the vicar of St Andrew’s Goldsworth Park said it

wouldn’t delay me very long, and it didn’t. This building dates to the 1980s

and it’s worth comparing it with St Barnabas, Iford, a 1960s church of which I

am very fond and which shares a similar plan, church upstairs and ancillary

rooms below: at Iford, however, a general Catholic ethos means the fittings

are massively and immovably built of concrete whereas at Goldsworth Park they

don’t even have a fixed font – one gets brought in from a cupboard when needed.

The baptismal pool is under the carpet of the café downstairs! Kate the vicar

(no point not using her real name) recounted how St John’s is setting up a Woking

network of ‘Gospel Churches’ which ‘Open Evangelical’ St Andrew’s definitely

hasn’t been asked to join.

St John’s was the first church built to serve Victorian

Woking: it was split off from St Peter’s, and then the other churches were split

off from it. It earns probably one of the rudest rebukes I’ve read in Pevsner’s

volumes: he points out that George Gilbert Scott didn’t include it in his list

of ‘ignoble’ churches built early in his career, but, Pevsner snorts, ‘he

should have’, and that’s his only remark on it. St John’s has had a resolutely

Evangelical tradition from its start, and so it has a spiky but all-wood

reredos behind the altar, and a modern baptismal pool beneath the chancel – but

there’s still some fancy mosaic-work around the altar, and the early 1900s

permitted a window of SS Margaret, Faith and Perpetua in memory of a

parishioner. In the rogues’ gallery of incumbents along the hallway, Revd

Hamilton, the great late-Victorian vicar of Woking, wears a white bowtie as a

signal that he’s having nothing to do with all this Oxford Movement nonsense.

My chum the vicar of St Andrew’s Goldsworth Park said it

wouldn’t delay me very long, and it didn’t. This building dates to the 1980s

and it’s worth comparing it with St Barnabas, Iford, a 1960s church of which I

am very fond and which shares a similar plan, church upstairs and ancillary

rooms below: at Iford, however, a general Catholic ethos means the fittings

are massively and immovably built of concrete whereas at Goldsworth Park they

don’t even have a fixed font – one gets brought in from a cupboard when needed.

The baptismal pool is under the carpet of the café downstairs! Kate the vicar

(no point not using her real name) recounted how St John’s is setting up a Woking

network of ‘Gospel Churches’ which ‘Open Evangelical’ St Andrew’s definitely

hasn’t been asked to join.

My chum the vicar of St Andrew’s Goldsworth Park said it

wouldn’t delay me very long, and it didn’t. This building dates to the 1980s

and it’s worth comparing it with St Barnabas, Iford, a 1960s church of which I

am very fond and which shares a similar plan, church upstairs and ancillary

rooms below: at Iford, however, a general Catholic ethos means the fittings

are massively and immovably built of concrete whereas at Goldsworth Park they

don’t even have a fixed font – one gets brought in from a cupboard when needed.

The baptismal pool is under the carpet of the café downstairs! Kate the vicar

(no point not using her real name) recounted how St John’s is setting up a Woking

network of ‘Gospel Churches’ which ‘Open Evangelical’ St Andrew’s definitely

hasn’t been asked to join.

With some relief I managed to reach St Mary’s, Horsell, the

villagey church on the north side of the town which I failed to get into a

couple of weeks ago. Here they definitely had a Catholic tradition which seems

to date from around the time of the major reconstruction of the church in 1890.

The old church had had a rood screen which was removed in 1840, but a new one

appears to have been put in either in 1890 when the chancel was rebuilt and

choir stalls, piscina and sedilia put in and the sanctuary floor decorated with

some rather nice marble and mosaic, or in 1909 when a side chapel was created.

That has a screen incorporating bits of an earlier one; at some stage an aumbry

for the reservation of the Blessed Sacrament appeared. Then sometime after 1970

the chancel screen was removed leaving just the rood beam topped by a cross,

and a dais and nave altar introduced. In all of this, Horsell’s history mirrors

Swanvale Halt’s almost exactly. But Horsell church’s most astonishing feature

is the sumptuous baptistery created in 1921 as a memorial to the son of a

former curate, killed in World War One. When I was at Lamford I went to a

curates’ training day at Horsell, and the then vicar told us how he was

desperate to move the font out of this curious and impracticably tiny space,

and that has now happened: the baptistery has become a crèche area and the font

now stands, much more sensibly, in the main body of the church.

Wednesday, 23 January 2019

Coming Around Again

Visiting S.D. yesterday we talked about routine in clerical

life. The knowledge that certain things happen at certain times in certain ways

is one of the things that makes for stability and calm in the spiritual life;

but a lot of clerical experience is a bit of a rigmarole - coming up with

words, words, words, often the same ones to the same people, and often to little apparent effect – and in those circumstances routine can evolve into

something which keeps God at arm’s length rather than something which shapes

our experience of him.

A friend sent me a copy of George Verwer’s Messiology, a

slim and simply-written book from 2015 arguing that God can use even the most

chaotic and contradictory situations and that we mustn’t assume that even

ministries and churches we don’t approve of can be channels of grace to those

involved in them. This is no startling news to pathetic liberal-Catholics like

me, though I dare say it may be to the conservative evangelicals who would form

the majority of Mr Verwer’s audience. What struck me rather than that was the

sense of freshness and energy coming from someone who’s been a missionary and

mission organiser for decades. I may not come from the same stable spiritually

or theologically, but I can see the grace in that.

At one level, all liturgy, from the most ‘spontaneous’

charismatic hand-waving jamboree to the contemplative solemnity of a Latin

mass, attempts to fix and replicate spiritual ecstasy. Of course it can’t do

this, at least not reliably, and anyone who seeks that will swiftly find only

dissatisfaction and eventually resentment. They may try to recapture it by

rearranging that liturgy or by going to another church, and again that may work

for a while and then fade. It’s the same thing that the addict seeks: the

energising, transforming rush of dopamine that creates ecstasy, literally ‘standing

outside oneself’: self-forgetting. But the brain learns to anticipate the

mechanism and as that happens it ceases to work.

What we need in order to keep forgetting ourselves is to be

surprised by those peak experiences, and you can’t engineer surprise. God is

infinitely surprising, but how do we keep exposing ourselves to that surprise? The

answer seems to lie in paying close and grateful attention to that which is not

us. The natural world is not us, and neither are other people. The liturgy

(whatever it’s like) is not us, and when we can forget our expectations and

demands and instead use it as material for prayer we do good work. Scripture,

in all its huge variety, is not us, and there are times when a verse we may

have read a score of times slaps us in the face with sudden relevance. In such

attention, and not in our own feelings of uplift or lack of it, lies the

blessing.

Monday, 21 January 2019

One Accord

The minister of the One Accord Church in Hornington has a distractingly pleasing view across the meadows from his office window. I was there on Sunday taking part in the annual United Service held on behalf of Churches Together locally. 'Here at One Accord we are a combination of four denominations', he told the assembled throng optimistically; well, technically it was two, the Methodists and the United Reformed Church, who joined together to form One Accord many years ago, although the URC was itself a combination of the Congregationalists and the Presbyterians, and a few Salvationists have started coming along since the Salvation Army Citadel in Hornington closed a couple of years ago, so that arguably makes up the four. Mind you, judged by that test Swanvale Halt Parish Church is a combination of loads of denominations. 'There are millions of services like this happening today,' went on the minister, and I thought that was a bit optimistic as well.

It was a bright, sunny morning on Sunday (as you can see) and the church was pleasingly full. Over the years I have posted repeatedly about the doings of our local branch of Churches Together (such as here, here, here and here) and you might have discerned my frustration with the organisation. The United Service is one thing - notwithstanding the generally watered-down liturgy, it's good for Christians themselves to get together in big groups and compromise - but several of the things Churches Together has been doing for twenty years and more do seem to be running into the ground. Our common efforts at 'witness to the community' are increasingly coming up against the obstacle that the secular world is more and more adrift from the Christian calendar and ways of doing things. Once upon a time, for instance, Churches Together ran a Christmas market culminating in the Blessing of the Crib and an ecumenical carol service in the old parish church in town. Then the Chamber of Commerce decided it wanted its own earlier street market to coincide with the turning-on of the Christmas lights. This year, the Chamber has objected to Churches Together closing the High Street for its charity-based Christmas market the weekend after the Chamber's own, and the Town Council has agreed, offering the churches the following Saturday instead, leaving some people positively intemperate. The clergy have for some years been arguing that the whole event needs to be rethought - what 'witness' is it to line the High Street with increasingly tatty charity stalls when the commercial ones look so much better, when far more people come to the Chamber of Commerce's market? - but the Town Council arranges its event schedule so far in advance that no sooner is one Christmas past that we are locked into planning for the next, a treadmill that leaves no time to think and evaluate.

Twenty to thirty years ago, the sight of Christian denominations co-operating in worship and community events was a spectacle which non-churchgoers found impressive in and of itself: I don't think it is any longer. It's become what everyone expects. Christians have to do a bit more than that to catch anyone's attention. What should that be? I don't think we have any clear idea.

But, for a morning, we could put all those thoughts aside. I could even forgive the non-alcoholic wine.

Saturday, 19 January 2019

When Sin is Not

After Hazel made her confession, we sat and talked a while over tea about sin. I said I thought that some matters serious Christians often felt worried about were not so much sins as normal features of the spiritual life and possibly needn't be confessed so much as talked through, although the confessional was perhaps one occasion for doing so. Distractions during prayer frequently comes up; I tend to feel that concentrated prayer is such an unnatural habit and requires so much effort that distraction is only to be expected and although it may arise from the sinful nature it probably should not be treated in this way. Particular and persistent distractions may reveal important matters of the soul that need dealing with, but that leads into the field of spiritual direction.

Then there's a whole category of faults and failings which begin with the words 'I have been insufficiently ...' this or that. These are usually free-floating expressions of self-dissatisfaction which are very unhelpful unless they can be tied down to some definite, concrete thought or act. We are all insufficient, especially if we measure ourselves against an unrealistic ideal. Then again, I remember the caution we all received at theological college that if we ever found ourselves hearing the confessions of members of religious orders we might be subjected to all sorts of stuff which we might not think was important in any way, and in those circumstances we should just take it as offered and treat it as the work of the Holy Spirit in that soul: consequently I don't want unreflectively to knock such thoughts down as irrelevant or neurotic.

In fact I'd entirely forgotten why I was visiting Hazel at all, so that's something to remember when I come to make my own Lenten confession ...

Then there's a whole category of faults and failings which begin with the words 'I have been insufficiently ...' this or that. These are usually free-floating expressions of self-dissatisfaction which are very unhelpful unless they can be tied down to some definite, concrete thought or act. We are all insufficient, especially if we measure ourselves against an unrealistic ideal. Then again, I remember the caution we all received at theological college that if we ever found ourselves hearing the confessions of members of religious orders we might be subjected to all sorts of stuff which we might not think was important in any way, and in those circumstances we should just take it as offered and treat it as the work of the Holy Spirit in that soul: consequently I don't want unreflectively to knock such thoughts down as irrelevant or neurotic.

In fact I'd entirely forgotten why I was visiting Hazel at all, so that's something to remember when I come to make my own Lenten confession ...

Thursday, 17 January 2019

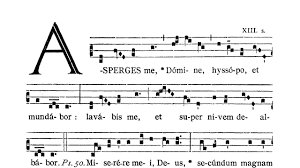

You Shall Purge Me With Hyssop

The feast of the Baptism of Christ last Sunday seemed an appropriate occasion for indulging in the picturesque rite called the asperges, the ceremonial sprinkling of water to remind Christians of their baptism. In the old Roman Rite (and in Anglican churches that borrowed from it) this used to be done every week, but with typical Anglican indiscipline we at Swanvale Halt do it when it takes the Rector's fancy.

As I picked up the holy water vat and sprinkler (aspersorium, if you want to be technical) and started down the aisle to fetch some water from the font, out of the corner of my eye I spotted the most Protestant member of the congregation making a very sharp exit out of the connecting door to the church hall. They re-entered once it was safe.

Oddly the asperges was one of the observances the Protestant Truth Society got very aerated about a century and more ago when they were campaigning against Catholic doings in Anglican churches. They sometimes even attempted to prosecute Anglo-Catholic clergy for assault on the grounds that their investigators had been sprinkled with water against their will, a charge the police listened to politely and did nothing about. Now, to claim you are allergic to incense may carry some conviction with it: to be allergic to water would be considerably more unusual.

(Image-Googling 'asperges' will lead you to many pictures of asparagus in French.)

As I picked up the holy water vat and sprinkler (aspersorium, if you want to be technical) and started down the aisle to fetch some water from the font, out of the corner of my eye I spotted the most Protestant member of the congregation making a very sharp exit out of the connecting door to the church hall. They re-entered once it was safe.

Oddly the asperges was one of the observances the Protestant Truth Society got very aerated about a century and more ago when they were campaigning against Catholic doings in Anglican churches. They sometimes even attempted to prosecute Anglo-Catholic clergy for assault on the grounds that their investigators had been sprinkled with water against their will, a charge the police listened to politely and did nothing about. Now, to claim you are allergic to incense may carry some conviction with it: to be allergic to water would be considerably more unusual.

(Image-Googling 'asperges' will lead you to many pictures of asparagus in French.)

Tuesday, 15 January 2019

Saint Spotted

My thanks are due today to Dr Abacus who noticed this fine icon of St Catherine in the chapel of Cumberland Lodge, which a friend of his serves as chaplain. I've never seen her depicted as veiled, which is interesting.

Sunday, 13 January 2019

Church Crawling Round Woking

Woking is a bit of an evangelical wasteland as far as churches are concerned but that doesn't mean there is no interest to be found in them. St Mary of Bethany, southwest of the town centre, is a church I've visited before, but not in the daylight; and coming upon its lumpen redbrick mass on a dull early afternoon is not the most aesthetically pleasing experience I've ever had. Within it turns out to be another of the churches that has reoriented itself 90 degrees and so has an altar against the long wall. The old chancel is relegated to the side, forming a chapel.

I've been in Christ Church for diocesan events umpteen times: it's big, well-equipped, and central, which is why it is so favoured. Yet until I had a determined poke around I'd never noticed the remaining signs of what it used to be. The great apsidal chancel has piscina and sedilia, so you could easily celebrate a Solemn High Mass here if you wanted to ...

... and stuck round a corner is this very pleasing reredos, another sub-Comper effort with the deep azure tone of a 15th-century manuscript ...

The reredos was installed behind the high altar in 1926, and the piscina and sedilia are part of the original fabric built in 1889. Now, it is true that late-Victorian church-building was dominated by High Church Gothic Revivalists and so these features would, perhaps, have been standard at the time, but Christ Church was a cheap job too - in so far as its size allowed - and I do wonder whether strict Low-Church principles and economy would both have conspired to rule them out. Such a consideration doesn't apply to the reredos. Either fitments of this kind were so much part and parcel of Anglicanism in the 1920s that nobody thought more of it, or the tradition of Christ Church has undergone an abrupt change at some point. (The original architect, just for interest, was WF Unsworth, who didn't build many churches but was responsible for the original Shakespeare Memorial Theatre at Stratford-upon-Avon, which looked like something out of The Castle of Otranto).

There are little elements at Christ Church which nod in a different direction. Everyone now seems to have a Paschal Candle to light during baptisms, while Rublev's Trinity icon is ubiquitous, no matter the tradition of the church:

A final point which illustrates how difficult it can be to gauge the sense of a church from its fittings and furniture. Christ Church has a modern altar, a near-circular table that sits in the middle of the great apse on a slate dais. Although the wood is of no great quality, you might see something very like this in a church of almost any tradition or denomination, from modern Roman Catholic to open-minded nonconformist.

I was lucky to meet the Director of Ordinands who, despite his surprise to see me, let me in to St Mary of Bethany to have a look around. I don't necessarily expect suburban evangelical Anglican churches to be open to visitors, so it was no shock that St Paul's, Oriental Road, was locked, but I was most disappointed not to be able to get in to St Mary's, Horsell, a far more villagey-type church on the north of the town. It looks as though I will have to arrange my crawling in advance.

PS. It suddenly struck me that Christ Church's baptismal pool must be under that wooden cross in the middle of the dais, so the altar must be capable of being slipped out of the way when need be. Very economical.

The biggest church in the town is Christ Church, a great redbrick barn of a place, though not as architecturally hard-headed as St Mary of Bethany, and which sits quite pleasingly in the shiny Jubilee Square in the centre of town. Here they haven't rearranged the interior because it's so wide it didn't need it, but it's clear that at Christ Church we are, liturgically speaking, back in the mindset of 18th-century Anglicanism, in which the church is a means of keeping people dry while they do religious things, rather than a sacred space in any sense. You'd be forgiven for thinking the piano and the drum kit are the main points of interest, although there is an altar, and we'll come to that in a minute.

I've been in Christ Church for diocesan events umpteen times: it's big, well-equipped, and central, which is why it is so favoured. Yet until I had a determined poke around I'd never noticed the remaining signs of what it used to be. The great apsidal chancel has piscina and sedilia, so you could easily celebrate a Solemn High Mass here if you wanted to ...

... and stuck round a corner is this very pleasing reredos, another sub-Comper effort with the deep azure tone of a 15th-century manuscript ...

The reredos was installed behind the high altar in 1926, and the piscina and sedilia are part of the original fabric built in 1889. Now, it is true that late-Victorian church-building was dominated by High Church Gothic Revivalists and so these features would, perhaps, have been standard at the time, but Christ Church was a cheap job too - in so far as its size allowed - and I do wonder whether strict Low-Church principles and economy would both have conspired to rule them out. Such a consideration doesn't apply to the reredos. Either fitments of this kind were so much part and parcel of Anglicanism in the 1920s that nobody thought more of it, or the tradition of Christ Church has undergone an abrupt change at some point. (The original architect, just for interest, was WF Unsworth, who didn't build many churches but was responsible for the original Shakespeare Memorial Theatre at Stratford-upon-Avon, which looked like something out of The Castle of Otranto).

There are little elements at Christ Church which nod in a different direction. Everyone now seems to have a Paschal Candle to light during baptisms, while Rublev's Trinity icon is ubiquitous, no matter the tradition of the church:

A final point which illustrates how difficult it can be to gauge the sense of a church from its fittings and furniture. Christ Church has a modern altar, a near-circular table that sits in the middle of the great apse on a slate dais. Although the wood is of no great quality, you might see something very like this in a church of almost any tradition or denomination, from modern Roman Catholic to open-minded nonconformist.

I was lucky to meet the Director of Ordinands who, despite his surprise to see me, let me in to St Mary of Bethany to have a look around. I don't necessarily expect suburban evangelical Anglican churches to be open to visitors, so it was no shock that St Paul's, Oriental Road, was locked, but I was most disappointed not to be able to get in to St Mary's, Horsell, a far more villagey-type church on the north of the town. It looks as though I will have to arrange my crawling in advance.

PS. It suddenly struck me that Christ Church's baptismal pool must be under that wooden cross in the middle of the dais, so the altar must be capable of being slipped out of the way when need be. Very economical.

Friday, 11 January 2019

What Goes Round

I am getting quite used to the lady who leads the termly 'Hot Topic' training sessions for school governors on behalf of Surrey County Council. About forty governors from a variety of schools (including three ordained people, I realised halfway through) spent a couple of hours in the Holiday Inn at Guildford as she breathlessly downloaded a mass of information some of which I managed to assimilate.

Do you remember how, a couple of years ago, I was in such a despondent state about the headlong, and forced, race towards academisation in English and Welsh schools? Now, we learn, this rush has come to an abrupt but untrumpeted halt. Perhaps as a result of some highly-publicised failures and the general realisation that they are not the market leaders they were purported to be, academies have gone very quiet. The Department for Education has stopped regarding a school being rated by OfStEd as 'Requiring Improvement' as the trigger for it to proceed towards academisation, but as a demonstration that it needs extra support. This is partly due to the departure of the former Secretary of State and partly to the Government's attention being absorbed by other matters: 'rather than OfStEd and the DFE being at loggerheads', we were told, 'OfStEd is in an increasingly influential position.'

Secondly, three years ago OfStEd was busy criticising schools for not concentrating sufficiently on the core curriculum and that other matters were secondary (and for 'secondary', read 'irrelevant'). Now, however, the inspectors have started saying the precise opposite, that children, especially in the earlier years of education, should be able to take part in a 'rich' curriculum that provides them with a rounded set of life experiences. We even now have the innovation of the 'Activity Passport', listing things it's good for children to have done between Reception and Year 6. Here's a flavour:

Reception: Taste a new fruit

Year 1: Look up at the stars on a clear night

Year 2: Get soaking wet in the rain

Year 3: Stay away from home for a night

Year 4: Skim stones

Year 5: Make and launch an air powered rocket

Year 6: Visit a local charity and find out how you can support them

The whole idea clearly arises from the popular perception that children are spending too much time sat in front of screens. Some of the tasks in fact quite sound demanding ('Choreograph a dance') but others bring a bit of a tear to the eye. The pointlessness and disutility of so many of them is one of the few things that has brought me much hope in humanity lately. I didn't expect that from an evening at the Holiday Inn in the care of Babcock 4S.

Do you remember how, a couple of years ago, I was in such a despondent state about the headlong, and forced, race towards academisation in English and Welsh schools? Now, we learn, this rush has come to an abrupt but untrumpeted halt. Perhaps as a result of some highly-publicised failures and the general realisation that they are not the market leaders they were purported to be, academies have gone very quiet. The Department for Education has stopped regarding a school being rated by OfStEd as 'Requiring Improvement' as the trigger for it to proceed towards academisation, but as a demonstration that it needs extra support. This is partly due to the departure of the former Secretary of State and partly to the Government's attention being absorbed by other matters: 'rather than OfStEd and the DFE being at loggerheads', we were told, 'OfStEd is in an increasingly influential position.'

Secondly, three years ago OfStEd was busy criticising schools for not concentrating sufficiently on the core curriculum and that other matters were secondary (and for 'secondary', read 'irrelevant'). Now, however, the inspectors have started saying the precise opposite, that children, especially in the earlier years of education, should be able to take part in a 'rich' curriculum that provides them with a rounded set of life experiences. We even now have the innovation of the 'Activity Passport', listing things it's good for children to have done between Reception and Year 6. Here's a flavour:

Reception: Taste a new fruit

Year 1: Look up at the stars on a clear night

Year 2: Get soaking wet in the rain

Year 3: Stay away from home for a night

Year 4: Skim stones

Year 5: Make and launch an air powered rocket

Year 6: Visit a local charity and find out how you can support them

The whole idea clearly arises from the popular perception that children are spending too much time sat in front of screens. Some of the tasks in fact quite sound demanding ('Choreograph a dance') but others bring a bit of a tear to the eye. The pointlessness and disutility of so many of them is one of the few things that has brought me much hope in humanity lately. I didn't expect that from an evening at the Holiday Inn in the care of Babcock 4S.

Wednesday, 9 January 2019

Midweek Disruption

Before I knew he was there, Bill had appeared outside the church porch, as he has virtually every Tuesday morning for decades to serve at the midweek mass (once upon a time we had services every day - but the Tuesday mass is the only one that survives). I was busy vandalising the noticeboard whose backing board has gradually buckled, discoloured and disintegrated until half of it is unusable: I wanted to strip it out so we could put notices directly onto the metal at the back, but found that the glue was tougher than I thought. I was left with a pile of bits of board to throw away.

Brenda had arrived at the same time. Bill was telling her, clearly in some distress, that he was lost. 'You're at the church, Bill, you're in the right place,' Brenda assured him. We both did. Brenda took Bill inside and sat him down in the Lady Chapel where we celebrate on Tuesday mornings. He was shaky and shivery and fiddled confusedly with his glasses - he should normally have two pairs but hadn't been wearing any when he arrived. We carried on with the service but Bill's presence is so perennial and steadfast that his agitation agitated us all. When it was over, some of the others took him to the old people's day centre for tea, but he was then whisked home and a doctor's visit later on confirmed that he had a chest infection, which I suppose we have to imagine accounted for his disorientation.

Bill, like so many others in the congregation, seems eternal even though you know they aren't. Every Tuesday he pours wine and water into the chalice I hold, and then washes my fingers after the communion, and I wonder how long he will be able to do so and how different things will seem when he isn't there. Nothing in this world lasts forever, yet we yearn for it to do so, or at least I do.

Brenda had arrived at the same time. Bill was telling her, clearly in some distress, that he was lost. 'You're at the church, Bill, you're in the right place,' Brenda assured him. We both did. Brenda took Bill inside and sat him down in the Lady Chapel where we celebrate on Tuesday mornings. He was shaky and shivery and fiddled confusedly with his glasses - he should normally have two pairs but hadn't been wearing any when he arrived. We carried on with the service but Bill's presence is so perennial and steadfast that his agitation agitated us all. When it was over, some of the others took him to the old people's day centre for tea, but he was then whisked home and a doctor's visit later on confirmed that he had a chest infection, which I suppose we have to imagine accounted for his disorientation.

Bill, like so many others in the congregation, seems eternal even though you know they aren't. Every Tuesday he pours wine and water into the chalice I hold, and then washes my fingers after the communion, and I wonder how long he will be able to do so and how different things will seem when he isn't there. Nothing in this world lasts forever, yet we yearn for it to do so, or at least I do.

Monday, 7 January 2019

Incensed

Epiphany is one of the occasions when we take the opportunity to use incense at Swanvale Halt, though it isn't quite as spectacular as the employment of the gigantic botafumeiro at Santiago, as illustrated here, not even when Fr C presided a few years ago and stoked the thurible more than usual, swirling the charcoal and incense pastilles around with the spoon. However that did make me wonder whether I was being a little stingy with the stuff, and on Sunday evening I gaily popped four pastilles, supplied by an Orthodox monastery not far away, into the pot. The resulting amount of smoke surprised even me, and I now know that four is enough to polish off the weaker of the parishioners. Subsequent chargings of the thurible were restricted to two.

You might say this is a small practical experiment. Following on from our discussion of science and humanism the other day, it occurred to me that while reason is of course a very good thing, and God can never be anything other than absolutely rational (if only we knew what the rational thing was), the scientific method is a different matter. Life is not a laboratory, and I don't mean that metaphorically. There are indeed circumstances in which we can determine what course of action to adopt by testing hypotheses, such as how much incense a particular congregation can stand wafting from a thurible. The thurible, the incense, and probably the people, remain the same from instance to instance: the variables are limited. But most of the time we inhabit immensely complex, nay chaotic, systems, and the accurate replication of experimental circumstances which is central to the scientific method becomes impossible. For instance, if you are a finance minister debating whether to adopt a particular fiscal strategy, you can't repeatedly test your guesses out on the level of an entire national economy and exclude all the variable circumstances which would make the resulting data meaningful. It is exactly those variable circumstances which make for so much dissension among economists (I wait for Dr Abacus to comment). There's only so much the scientific method can do: and beyond it, we're left with the arguable.

You might say this is a small practical experiment. Following on from our discussion of science and humanism the other day, it occurred to me that while reason is of course a very good thing, and God can never be anything other than absolutely rational (if only we knew what the rational thing was), the scientific method is a different matter. Life is not a laboratory, and I don't mean that metaphorically. There are indeed circumstances in which we can determine what course of action to adopt by testing hypotheses, such as how much incense a particular congregation can stand wafting from a thurible. The thurible, the incense, and probably the people, remain the same from instance to instance: the variables are limited. But most of the time we inhabit immensely complex, nay chaotic, systems, and the accurate replication of experimental circumstances which is central to the scientific method becomes impossible. For instance, if you are a finance minister debating whether to adopt a particular fiscal strategy, you can't repeatedly test your guesses out on the level of an entire national economy and exclude all the variable circumstances which would make the resulting data meaningful. It is exactly those variable circumstances which make for so much dissension among economists (I wait for Dr Abacus to comment). There's only so much the scientific method can do: and beyond it, we're left with the arguable.

Labels:

Christianity and society,

Epiphany,

liturgical,

science

Saturday, 5 January 2019

Farnham and About

My week off between New Year and Epiphany came to a conclusion yesterday in a walk around Farnham. It was a bright, chilly late morning and early afternoon, and the fairly short walk - only an hour and a half or so - took me around the hills northwest of that small Surrey town, past timber-framed farmhouses glimpsed across the fields, and more modern structures such as the 1930s - perhaps - Cedar House.

I took in visits to a couple of churches. Although St Francis's, Byworth, was shut, it's a perfect example of the sort of small estate churches being built during Anglicanism's boom-time of the 1950s, when a moderate sort of Catholicism was the natural environment for the Church of England. It has a bell, a statue of the Saint by the door, and an altar hung with a brocade frontal.

Its mother-church, the medieval St Andrew's in town, is intriguing because it seems to suggest successive waves of Catholicisation, beginning with a restoration of the chancel in 1848, whose tide is now ebbing. A Lady Chapel was created in 1909 and the altar brought forward in 1959, a very early date for a change like that. In the early 2000s an internal suite of meeting rooms was created by clearing out the pews and creating a wood and glass box at the west end of the nave. I couldn't find any date for this splendid sort-of sub-Comper reredos, which now sits behind the old high altar at the far end of the church. I'm guessing it can't be earlier than 1910 (and perhaps not much later).

Finally I called in at Farnham Museum, set in a Georgian town house on the main street. Its staircase is apparently very highly regarded:

The collection isn't vast, but every local museum furnishes some surprises and Farnham's is no exception. I will spare you the taxidermy diorama of red squirrels playing cards, but thought I would share John Verney's The Three Graces Playing Croquet in the Garden of Farnham Castle which was definitely a surprise to me, at any rate. Splendidly the Museum has it available in postcard form. Mr Verney is on record as saying that 'the addition of a clergyman raises the tone of any painting.'

I took in visits to a couple of churches. Although St Francis's, Byworth, was shut, it's a perfect example of the sort of small estate churches being built during Anglicanism's boom-time of the 1950s, when a moderate sort of Catholicism was the natural environment for the Church of England. It has a bell, a statue of the Saint by the door, and an altar hung with a brocade frontal.

Its mother-church, the medieval St Andrew's in town, is intriguing because it seems to suggest successive waves of Catholicisation, beginning with a restoration of the chancel in 1848, whose tide is now ebbing. A Lady Chapel was created in 1909 and the altar brought forward in 1959, a very early date for a change like that. In the early 2000s an internal suite of meeting rooms was created by clearing out the pews and creating a wood and glass box at the west end of the nave. I couldn't find any date for this splendid sort-of sub-Comper reredos, which now sits behind the old high altar at the far end of the church. I'm guessing it can't be earlier than 1910 (and perhaps not much later).

Finally I called in at Farnham Museum, set in a Georgian town house on the main street. Its staircase is apparently very highly regarded:

The collection isn't vast, but every local museum furnishes some surprises and Farnham's is no exception. I will spare you the taxidermy diorama of red squirrels playing cards, but thought I would share John Verney's The Three Graces Playing Croquet in the Garden of Farnham Castle which was definitely a surprise to me, at any rate. Splendidly the Museum has it available in postcard form. Mr Verney is on record as saying that 'the addition of a clergyman raises the tone of any painting.'

Labels:

architecture,

art,

art deco,

church interiors,

museums,

walks

Thursday, 3 January 2019

Must Try Harder

As an ex-atheist I still have some vestigial sympathy with

unbelievers, but I do wish they made it easier. This week, Radio 4 is

broadcasting extracts from Stephen Hawking’s final book, Brief Answers to the

Big Questions, and on Wednesday morning the words of the late physicist

concerned creation and the Creator and why there isn’t one. I know the book is

‘popular science’ and therefore watered down from the real thing, but really.

Hawking relates how the ‘space’ for God has gradually shrunk as science has

provided better explanations for natural phenomena: the beauty of science is

that it reveals ‘the laws of nature’ behind what we observe, rather than the

arbitrary fiat of a deity. All that’s left to God, says Hawking, is kicking the

whole thing off, and even that loophole seems about to vanish. When we enter

the subatomic realm of quantum mechanics, particles appear and disappear randomly, and this provides a model of how the universe itself, originally

subatomically tiny and almost infinitely dense, might have suddenly appeared

without explanation and without cause. Furthermore, says Hawking, since time

itself only came into existence as the universe expanded in the Big Bang, and

causation is a function of time, our natural curiosity as to what ‘explains’

its arrival is misplaced: no time, no need for explanation. The universe merely

is.

Now, if the beauty of science lies in its revelation of

natural laws, where the apparent randomness of the quantum world leaves it I

can’t imagine. If, as one humanist contributor to my friend the Heresiarch’s former

blog once commented dismissively and reductively, ‘stuff pops into existence

all the time’, that means that at a fundamental level there is no ‘law’; unless

there are laws that we haven’t worked out yet, which would make the randomness

apparent rather than real (as Einstein insisted, so I understand). And the 'stuff' that 'pops into existence' somehow never turns out to be an infant universe: that event was, as far as we know, unique. Observable subatomic particles (appear to) 'pop into existence' within a pre-existing system rather than outside it, so the two events are not analogous. Meanwhile, disposing of the notion of causation by

abolishing time is philosophical sleight-of-hand and nothing more. This is all

quite apart from the jejune concept that the only reason for believing in God

is that we can’t think of a better explanation for the origin of the universe,

or thunder, or the existence of cats (whether or not indeterminately alive or dead). ‘There will always be believers in God,

because there will always be people who want that kind of comfort’, concludes

Hawking. There will always be people willing to trade their intellectual

integrity for emotional security, because that’s what it’s all about. Thanks.

One of my Christmas gifts was Dr David Layton’s book The

Humanism of Dr Who, which as an old Whovian caught my eye. Any attempt to draw spiritual lessons from the long-running fantasy series (‘sci-fi’ is a bit of an

insult to that genre) comes up against the fact that the good Doctor’s

world-view is defiantly secular-humanist, so this book must have been an easier

write. I’ve only just begun it, but did scan first through the chapter on

religion. And there we find the contention ‘religious “belief” requires “the

leap of faith”, the trust that a statement is true apart from any evidence or

reason in its support. The religious point of view is that is a belief is held

strongly enough, it is true’. This kind of – forgive me – garbage is regularly

trotted out by atheists who clearly have never paid attention to religion and

religious people at all. Remember, I decided I believed in God on the basis of

evidence. I admit gladly that my previous experience and predispositions may

have played a role in that decision; that another person with different

experience and predispositions might have decided entirely differently on the

basis of exactly the same evidence; and that there indeed comes a point where

you cannot determine the existence or otherwise of God simply on the basis of

that evidence. But that’s what most of life is like: you can’t prove beyond any

doubt that a chair is there but that doesn’t stop most people sitting down with

a cup of tea. Faith is not exercised on the basis of no evidence at all. Anyone who claims it is isn’t paying attention to the real

experience of religion and probably doesn’t want to.

The third atheist outlook I’ve dealt with over this holiday

is that of Arthur C Clarke who I looked up after hearing his name and realising

I didn’t know that much about him. He apparently ‘could not forgive religions

for their inability to prevent atrocities and wars’. My old doctrine tutor said

that the best argument for the non-existence of God was the behaviour of

Christians, and that I can still absolutely go along with.

Tuesday, 1 January 2019

Changing the Calendar

I don't know how Swanvale Halt saw in the New Year this time round, as I was in London having dinner with Citizen Globaljumper who is over for a few days from Cairo where he is publications manager for the regional office of the World Health Organisation. We were meeting in Archway, not far away from the flat he used to share with his brother. I couldn't remember what the area around the Underground station used to be like, but it is currently what I suppose ought to be called a plaza with a few seats and a lot of empty space where, my friend tells me, there was a particularly hazardous road junction. The restaurant we went to was nearly fully booked although we were squeezed onto a side table (and fed some very pleasing fare), but the Angel, Highgate, our designated drinking hole afterwards, was surprisingly quiet.

Abandoning Mr Globaljumper at Archway I went to The Albany in Great Portland Street where Mal and a couple of the other longest-standing DJs in the Goth world had decided to stage a small event while the rest of that world gravitated towards Slimelight. Small it had to be, because the Albany's basement can't fit that many people. 'Tarantella' is a continuation of a string of occasional club nights Mal has run with others over the years. It reminded me a bit of how Tanz Macabre was in its Soho days though without the Arts Theatre Club's decadent elegance. Moments before midnight the music ceased and the PA system broadcast the bongs - isn't Big Ben still out of action at the moment? or perhaps it was turned on again for the occasion? - and we all toasted the year to come, hoping, as one always does, that it's better in some respects than the one past. I enjoy New Year and the sense of hope it brings, though of course January 1st and the clicking over of a date means nothing at all: the emotion and the aspiration are real enough.

The journey back to Surrey was by no means as disagreeable as it had been in earlier years. The gyratory system around Waterloo didn't take us as far away from the station and the train, though crowded, was quite civilised. The guard kept up her announcements before and after each station doggedly, reminding passengers to check the folk around them weren't sleeping past their disembarkation point, and apologising for 'sounding like a broken record'. I thought she was perhaps a bit hysterical with weariness, but even that made the experience more tolerable. A Happy New Year to you!

Abandoning Mr Globaljumper at Archway I went to The Albany in Great Portland Street where Mal and a couple of the other longest-standing DJs in the Goth world had decided to stage a small event while the rest of that world gravitated towards Slimelight. Small it had to be, because the Albany's basement can't fit that many people. 'Tarantella' is a continuation of a string of occasional club nights Mal has run with others over the years. It reminded me a bit of how Tanz Macabre was in its Soho days though without the Arts Theatre Club's decadent elegance. Moments before midnight the music ceased and the PA system broadcast the bongs - isn't Big Ben still out of action at the moment? or perhaps it was turned on again for the occasion? - and we all toasted the year to come, hoping, as one always does, that it's better in some respects than the one past. I enjoy New Year and the sense of hope it brings, though of course January 1st and the clicking over of a date means nothing at all: the emotion and the aspiration are real enough.

The journey back to Surrey was by no means as disagreeable as it had been in earlier years. The gyratory system around Waterloo didn't take us as far away from the station and the train, though crowded, was quite civilised. The guard kept up her announcements before and after each station doggedly, reminding passengers to check the folk around them weren't sleeping past their disembarkation point, and apologising for 'sounding like a broken record'. I thought she was perhaps a bit hysterical with weariness, but even that made the experience more tolerable. A Happy New Year to you!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)