It was one of the most anxious days of the year at Swanvale Halt church: the Infant School Palm Service. The anxiety arises not from the children, who despite their excitement are generally very well-behaved, but from the cause of their excitement - a brace of donkeys.

The donkeys are well-behaved too; at least, they've never been anything else. They have been coming to the church on the Wednesday or Thursday in the last week of the Spring term to take part in the Palm Service for years, and nothing untoward has ever taken place. The problem is that, while they used to reside in a field in a nearby village, now they live quite a drive away in Liphook, and have to make their way north along the A3 just at the time many, many people are making the same journey. And anything can happen.

Should the donkeys not make it, the children would be most disappointed. But it doesn't end there. The main problem is finding parking for them and their trailer, given the busy-ness of the centre of Swanvale Halt these days, made worse by the fact that a new pipeline is being run to a block of sheltered housing next to the church, occupying the parking spaces there. So while depositing Ms Formerly Aldgate back at her flat last night I put out our bollards politely asking drivers to please 'leave this space for donkeys' and hoped for the best. They were still in place this morning but there were a stubborn two cars parked in just the position to make it awkward for the trailer to park, and when, to my delight, it appeared further down the street, and I removed the bollards so Mr & Mrs Donkey-Wrangler could park, instead they turned into the driveway of said sheltered housing and another car nipped in to the space where the bollards had been.

Of course it was all OK. The Donkey-Wranglers negotiated with the workmen and the children followed the donkeys around the churchyard waving their palm crosses before going into the church for the rest of the service. The headmistress has a new speaker to link to her phone for playing the children's songs which despite its exceedingly modest size can fill the whole church. I sat listening to Out of the Ark's 'Hosanna to King Jesus' being sung by dozens of small voices and kept my eyes fixed on the rafters above, in case emotion got the better of me.

PS. The children went back to school to mark a 'pause day', in which the curriculum was set to one side to concentrate on storytelling, prayers, quiet times, and other activities looking towards Easter. It takes quite some confidence on the part of a head teacher to do that and I think it's great.

Thursday, 30 March 2017

Tuesday, 28 March 2017

Moving Church Antiques

This photo from the Spring of 2014 is something of an historic document now. Over the years I've been a regular customer at Church Antiques at Walton-on-Thames, buying several sets of discarded vestments and other ecclesiastical impedimenta either for me or the church. Even when I didn't buy anything it was always fun to visit and poke around the dusty tables of statuary and lamps. Very occasionally I've been able to contribute to the amusement arcade as I did last August.

On my way back from Malling Abbey last week I thought it might be good for Marion our curate to have a rose-pink stole for Mothering Sunday, so we were colour-co-ordinated. Much to my surprise, I arrived at Riverbrook Farm just north of Walton to find the gates chained shut. Church Antiques has decamped to Betchworth, though I don't remember this being much publicised. I haven't been to the new site yet: it might be harder to get to, which would probably be a good thing for me, spiritually.

Sunday, 26 March 2017

Ghosts of Business Past

A strangely fascinating sight around a community are the marks you occasionally see of the advertising signs of long-past businesses. Names and details of shops and retailers painted directly onto brickwork was once very common: I ought to try and work out when it began to fall out of fashion. Perhaps the ability to print signs rather than have them painted was the crucial change, but I get the impression the habit had disappeared long before then. Faded and usually fragmentary, they are spectral reminders of a different state of affairs.

Swanvale Halt, unusually for a place of its kind, still has a number of shops and businesses, though many fewer than it used to. Next to the Post Office a building which having lain derelict for many years is at last being converted into a dwelling. Fifteen years or so past it was a small bakery, though my suggestion that the new house should be called La Vielle Patisserie has not met with much favour: as it's going to be the new home of the Patels from the Post Office itself our Lay Reader Lillian argued that name should be rendered into Hindi rather than French.

I say, it's being converted: there's actually not a lot of it left, beyond the side walls of the ground storey. On the outer face of one of the walls is this phantom lettering. There are at least three different letter styles in the sign and I find it impossible to make any sense of it. I'm not suggesting it should have a preservation order slapped on it, but I will miss this tiny mark of continuity when it's inevitably covered up.

-------------------------

PS. It wasn't covered up in the end, it was demolished with the rest of the wall.

Friday, 24 March 2017

Support Network

Fortified by theme parks and new friendships, Cylene the Goth has been doing better of late than for a long while, but she still has her moments. At one of them, recently, music came to her aid - or Spotify's algorithms did, pointing her towards 'Bravery' by Assemblage23. 'I'm really, really pleased that there are as many songs like this as there are in the Goth/industrial scene,' she wrote in Another Place. 'I always do love proudly boasting how for a bunch of "scary satanic rejects" we've got good manners and are very good at supporting each other without judgement'.

The song itself isn't to my taste, but for anyone with mental health issues simply having those issues acknowledged without criticism by someone else, whether you know them or whether they're at a distance, is a step towards change. Of course the mental health 'system' is naturally dedicated to healing, but too often the sense its users get is that they are being judged and criticised by people whose insights into their condition are clinical and analytic rather than sympathetic, and that there's an unspoken verdict that they're not trying hard enough to be normal. Acceptance by one's peers is very different.

As if it needed stating again, Cylene's experience suggests how the Goth world can function as a place of healing and support rather than exacerbating and exploiting people's negative tendencies as those outside it often assume. Back in the days when our friend Karla was the organiser of the London Goth Meetup, the introductory blurb on the group's webpage warned that new members would not find misery and introspection there and if that was what they were looking for, they might try elsewhere. I know what she was getting at, trying to combat the image of Goths that too many outsiders have; but a place of sanctuary, and growth, is exactly what many damaged souls find in it.

The song itself isn't to my taste, but for anyone with mental health issues simply having those issues acknowledged without criticism by someone else, whether you know them or whether they're at a distance, is a step towards change. Of course the mental health 'system' is naturally dedicated to healing, but too often the sense its users get is that they are being judged and criticised by people whose insights into their condition are clinical and analytic rather than sympathetic, and that there's an unspoken verdict that they're not trying hard enough to be normal. Acceptance by one's peers is very different.

As if it needed stating again, Cylene's experience suggests how the Goth world can function as a place of healing and support rather than exacerbating and exploiting people's negative tendencies as those outside it often assume. Back in the days when our friend Karla was the organiser of the London Goth Meetup, the introductory blurb on the group's webpage warned that new members would not find misery and introspection there and if that was what they were looking for, they might try elsewhere. I know what she was getting at, trying to combat the image of Goths that too many outsiders have; but a place of sanctuary, and growth, is exactly what many damaged souls find in it.

Wednesday, 22 March 2017

Back to Malling

You might think that religious communities never change,

from decade to decade – and even century to century – and that perhaps that’s

their point. But they do, and last year I missed out on my annual retreat to

Malling Abbey because the holy Sisters were reorganising the guest

accommodation, and in fact I was too woefully disorganised to get in anywhere

else either. It was a relief to be back this year for a couple of days.

The guests now inhabit four nice new rooms over the Abbey

cloister, looking out onto the Cloister Garth with its fountain and church bell

tower behind. The old Guesthouse, which comprised many more rooms, had a

certain spatchcock charm, but I won’t miss scuttling along the hallway in my

pyjamas wondering who I might meet on my way to the shower, and not being able

to move around the room without the floor creaking so much one risked waking

the resident next door. It used to be pleasant to have meals cooked for us, but

I don’t resent the Sisters deciding that aspect of Benedictine hospitality is a

bit beyond them now, and self-catering just requires a little organisation.

Frankly I never went to Malling for the food, it has to be said; although a few

years ago on the Feast of St Benedict we were treated to rather a nice banoffee

pie.

The old Guesthouse is now occupied by the St Benedict’s

Centre, a theological and spiritual resource for St Augustine’s College,

Canterbury, with a new library on the opposite side of the path. There’s a big

car park beyond what was a tall hedge, and a path between the two along which

people come and go, making the site feel less isolated than it once did. The

Pilgrim Chapel’s quaint rush-seated chairs have been replaced by upholstered

red ones, aesthetically horrendous but far more comfortable. There are

entry-code doors and PIR-operated lights so you run less risk of serious injury

moving around the Abbey at night (of course once upon a time it was assumed you

wouldn’t be moving around at night)

and so you no longer have to ask the Guest Sister for permission to be outside

the enclosure after Compline. Change has come to perpetual Malling; and

although as outsiders none of us knows quite what conversations the community

went through before they opened themselves up in this way, it must have taken

quite some mental restructuring, some reassessment of what ‘Benedictine

hospitality’ actually meant.

My time there was good. I arrived in rain, spent Tuesday in

lovely sunshine, and left in rain again: seeing the Abbey in its different

meteorological moods gives some sense of what living there is like. I managed

to pray about things I need to amend in my life, aspects of the life of

Swanvale Halt church, and the centrality of the Blessed Sacrament as I sat in

the Pilgrim Chapel with the rain beating on the windows. I got through Michael

Ramsey’s The Gospel and the Catholic

Church, which reminded me why I read it first ten years ago, and Rowan

Williams’s Silence and Honey Cakes

about the spirituality of the Desert Fathers. I’ve read that before, too, but

it hit home far deeper this time. The book is more than it first appears: far

from being just an examination of a time in the past life of the Church, it’s a

politely and covertly stated manifesto for what the Church should be now:

certainly not adopting too much the models of the manager and theologies of

leadership (as though Jesus ever talked of any such thing!), but based rather

on the words of St Antony the Great: ‘Our life and death is with our neighbour.

If we win our brother we win God. If we cause our brother to stumble we have

sinned against Christ.’ Of course he takes a book, albeit not a long one, to

open that statement out. I realised afresh how superficial and silly my

spiritual life can be and the nonsense that sometimes characterises my

thinking. I think I have a new glimpse of the reason why there are priests, and

why parish priests are in so perilous a spiritual position. I walked to St

Leonard’s Well and found it dry as it sometimes is (it was in full flow in

2015).

And I was very grateful for it all, for the rain and for the

sun and for these old stones and for Benedictine hospitality, whatever it means

in the 21st century.

Monday, 20 March 2017

Swanvale Halt Film Club: Three Old Horrors: The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920), Nosferatu (1922), The Haunting (1963)

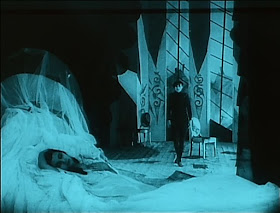

No undiscovered gems this time: these three movies are pretty well known to most people interested in film generally and the Gothic strain within it in particular.

Of the two creaky silents, we found Caligari (which neither of us had seen before) the rather superior of the two, despite its very deliberate weirdness: so much so that I wondered whether the version of Nosferatu we were watching was some unrestored print. The scene-changing is so choppy it borders on the inept. Although Caligari is determined to be odd and non-realistic, Nosferatu has an awful lot of irrelevance packed in: given the lack of time available to tell the story (such as it is) you have to ask why FW Murnau wasted so much footage showing us Dr Van Helsing playing with carnivorous polyps with his students, Harker making his way ponderously home across streams and slopes, and Nina mooning about the Westernras' house or the beach waiting for him. The action jerks restlessly from shot to shot in a way which is possibly intended to escalate tension and urgency but without a decent score to help, it doesn't work. Music can make or break a silent film, and while the score for the verison of Caligari we saw was excellent, the Nosferatu music was clunkingly inappropriate and at times veered in the direction of 'Charlie Chaplin meets the Vampires'. There are some great shots, however: I like the view Nina sees from her window of a procession of coffins being carried along the street as the vampiric plague ravages Bremen. In Caligari, the sequence of Cesare the somnambulist advancing from a window towards the sleeping Jane is still creepy after nearly a century, and you can see how it feeds into subsequent horror cinema.

Of the two creaky silents, we found Caligari (which neither of us had seen before) the rather superior of the two, despite its very deliberate weirdness: so much so that I wondered whether the version of Nosferatu we were watching was some unrestored print. The scene-changing is so choppy it borders on the inept. Although Caligari is determined to be odd and non-realistic, Nosferatu has an awful lot of irrelevance packed in: given the lack of time available to tell the story (such as it is) you have to ask why FW Murnau wasted so much footage showing us Dr Van Helsing playing with carnivorous polyps with his students, Harker making his way ponderously home across streams and slopes, and Nina mooning about the Westernras' house or the beach waiting for him. The action jerks restlessly from shot to shot in a way which is possibly intended to escalate tension and urgency but without a decent score to help, it doesn't work. Music can make or break a silent film, and while the score for the verison of Caligari we saw was excellent, the Nosferatu music was clunkingly inappropriate and at times veered in the direction of 'Charlie Chaplin meets the Vampires'. There are some great shots, however: I like the view Nina sees from her window of a procession of coffins being carried along the street as the vampiric plague ravages Bremen. In Caligari, the sequence of Cesare the somnambulist advancing from a window towards the sleeping Jane is still creepy after nearly a century, and you can see how it feeds into subsequent horror cinema.

Naturally the more modern The Haunting is a different matter. I've seen this umpteen times before and always enjoy it, while it was new to Ms Formerly Aldgate. Some of the acting is a bit stilted, but the whole thing is so stylish and reticent - you never see anything particularly horrific and the worst manifestations that befall the protagonists are knockings and turning doorknobs - that any small defects are completely overcome. I hadn't realised quite how sophisticated the camerawork is, constantly exciting and unusual without being distracting from what's going on. Not a masterpiece, perhaps, but endlessly entertaining and properly eerie.

Saturday, 18 March 2017

#EverydaySexism

Passing the charity shop on my way to church, a little girl

of about 3 and a middle-aged lady were looking in the window, having a

conversation about a dress. Then the little girl pointed out a train set.

'Yes', says the lady. 'a choo-choo train. But that's for boys, isn't it?'

I moved on before they started discussing the pole-dancing kit next to it.

A Lack of Humour

In Poole Cemetery, not far away from where this picture seems to have been taken, are my dad's and grandparents' graves. I don't go there very often; my grandad died a long time ago, and my nan was six weeks off her 100th birthday, and I don't feel the loss of them that keenly. As for my dad, when I think about his death my predominant feeling, even after five years, is anger at the injustice and squalor of it rather than any personal lack it leaves me with. My mum experiences the sense of loss much more acutely, and is often at the cemetery to clean the gravestones and reconnect with her parents and my dad, when her health allows her.

She was there at the start of this week, and found the area around the graves roped off with hazard tape 'like there had been a murder'. It seems the Council contractors had been tree-felling and the logs from a large pine were stacked behind the row of graves. She discovered nan and grandad's grave was covered with branches and twigs and there were wood-chippings everywhere. The gravestones themselves were spattered with orange pine resin. It looked, difficult though it is to credit, as though the logs had been cut up while resting on the graves themselves. The flower-holder on my grandparents' grave had been broken. It wasn't as though they were old graves that no-one visits: the dates are 2012 and 2014.

One of the cemetery staff was nearby and noticed my mum's distress. He found the state of the area as shocking as she did. He tried to clear up the mess, ineffectually. 'I'm sorry, it's all embedded in the stone chippings. You'll have to clear the graves completely and wash it out. And the resin needs more than just water to clean it off.' He would speak to the Parks Department about it. Mum had enough resolve to call the Council herself when she got home, and then me. 'I can't manage this, if we need to do anything more you and your sister will have to deal with it.'

As I say, I'm not a frequent visitor to the cemetery: I go with my mum occasionally when I'm down in Dorset, perhaps once a year. But if the contractors could be so unprofessional and careless in this case they could be so again, so I was prepared to make a lot of fuss indeed.

In the end it wasn't necessary: two days later mum had a call from Poole Council apologising for what had happened and assuring her that the contractors would make the damage good, and I thank God for someone having the sensitivity to see the problem. We 'professionals' endlessly run the risk of getting blasé about the work we do day by day, and have to remember that for those on the receiving end the scale of value is very different.

She was there at the start of this week, and found the area around the graves roped off with hazard tape 'like there had been a murder'. It seems the Council contractors had been tree-felling and the logs from a large pine were stacked behind the row of graves. She discovered nan and grandad's grave was covered with branches and twigs and there were wood-chippings everywhere. The gravestones themselves were spattered with orange pine resin. It looked, difficult though it is to credit, as though the logs had been cut up while resting on the graves themselves. The flower-holder on my grandparents' grave had been broken. It wasn't as though they were old graves that no-one visits: the dates are 2012 and 2014.

One of the cemetery staff was nearby and noticed my mum's distress. He found the state of the area as shocking as she did. He tried to clear up the mess, ineffectually. 'I'm sorry, it's all embedded in the stone chippings. You'll have to clear the graves completely and wash it out. And the resin needs more than just water to clean it off.' He would speak to the Parks Department about it. Mum had enough resolve to call the Council herself when she got home, and then me. 'I can't manage this, if we need to do anything more you and your sister will have to deal with it.'

As I say, I'm not a frequent visitor to the cemetery: I go with my mum occasionally when I'm down in Dorset, perhaps once a year. But if the contractors could be so unprofessional and careless in this case they could be so again, so I was prepared to make a lot of fuss indeed.

In the end it wasn't necessary: two days later mum had a call from Poole Council apologising for what had happened and assuring her that the contractors would make the damage good, and I thank God for someone having the sensitivity to see the problem. We 'professionals' endlessly run the risk of getting blasé about the work we do day by day, and have to remember that for those on the receiving end the scale of value is very different.

Thursday, 16 March 2017

What the Garden Says

Today it was about time to mow the lawn for the first occasion this year. I say 'lawn' although most of it is either moss or beds of lesser celandine at the moment, and I avoided the flowering primroses, too.

Isaiah the prophet says 'How beautiful on the mountains are the feet of those who bring good news!' The Rectory garden is steep but not exactly mountainous, and the camellias don't have feet in any normal sense, but they are indeed beautiful and always seem like a sudden burst of shocking-pink joy against the old wall next to the grapevine. If they bring any news, it's only 'we're still alive and so are you!' which is probably good, at least for most of the people I know.

Isaiah the prophet says 'How beautiful on the mountains are the feet of those who bring good news!' The Rectory garden is steep but not exactly mountainous, and the camellias don't have feet in any normal sense, but they are indeed beautiful and always seem like a sudden burst of shocking-pink joy against the old wall next to the grapevine. If they bring any news, it's only 'we're still alive and so are you!' which is probably good, at least for most of the people I know.

Tuesday, 14 March 2017

Gender Coded Church

On Wednesday it was the first instalment of my Lent course

for the church: everyone there was female apart from me and one chap, who is an

ordinand with us on placement and so doesn’t count as an ordinary human being any

more than I do. Then on Saturday curate Marion led a Quiet Morning, and that

was completely female, too. ‘Why men don’t go to church’ is a perennial

question: in fact Swanvale Halt parish emerged from its ‘church survey’ a

couple of years ago (part of the Mission Planning process) as less sexually

unbalanced as many churches are, but unbalanced it nevertheless is, and the

further you get into ‘churchy’ activity the more the inequality is apparent.

The typical answers to the question circle around the

accusation that church and what happens in it is too girly to appeal to chaps:

all that stuff about emotion, self-doubt, and submissiveness. You find this

talked about quite a lot at the evangelical end of the spectrum, and people

counteract it with the opposite sort of language: battle, struggle, manliness.

There are severe problems with adopting this tactic, however; not everyone responds at all well to it, and furthermore even

Christian pastors worried about getting men to take part in church know full

well that they necessarily have to engage with all the girly stuff at some

point: it’s inescapable because that rhetoric is at the centre of Christian

experience. So you end up with, for instance, worship songs like Martin Smith’s

‘Men of Faith’ from 1995, which tries, awkwardly, to have it all – combining a profoundly

gendered vision of Christian life while acknowledging that both sexes are

‘broken’:

Men of

faith, rise up and sing,

Of the great

and glorious King;

You are strong

when you feel weak,

In your

brokenness complete.

Women of the

truth,

Stand and

sing to broken hearts,

Who can know

the healing power

Of our glorious King of love.

I found myself wondering whether this wasn’t looking at the

matter from the wrong end. Is it perhaps the case that men engage with religion

less because religion is less 'important' – meaning that its utility isn’t

obvious and is hard to demonstrate – and activities perceived as less important

are socially delegated to women? Nowadays the idea that men are always the sole

breadwinners in the family unit is hopelessly outdated, and yet the idea of paid work is still coded as male. Other things which might

distract men from church, from popular hobbies to team sports, are also coded

as male regardless of how many women participate in them. Society has indeed shifted

far enough to regard spending time with one’s children as intrinsic to being a

good parent, of either sex, but at that point another social pressure kicks in and fathers’

time with their children usually involves doing things the children will find

fun: except for the especially pious, religion isn’t important enough to compel

parents to make their children join

in with it.

Women disproportionately do church because it isn’t

important. Naturally the converse is true: that whatever women do is

unimportant, and so church is unimportant because women do it

disproportionately. While mum takes the children to worship on Sunday (or Messy

Church, perhaps), dad will usually find – even if his levels of belief are no different

from hers – that almost anything else is a more worthwhile use of his available time.

Of course I don’t have any evidence of this: it’s buried and

inarticulate, which is why it would be very hard to winkle out and bring into

the light. That doesn’t mean it’s incorrect.

Sunday, 12 March 2017

Blessed Incoherence

Poor Fr Philip North is making something of a career out of

not being appointed bishop of various places. A few years ago he wasn’t

appointed Bishop of Whitby; now he has withdrawn his name from consideration as

the next Bishop of Sheffield. In between, he did manage to become Bishop of

Burnley, but one out of three isn’t a good average.

I met Philip North once when he came to St Stephen’s House

while I was studying there. Everyone thinks he’s a pretty good egg. The trouble

is that he’s the wrong sort of egg for some people, and although he’s easily

the most personable prominent traditionalist Anglo-Catholic in the Church of

England – which is why the hierarchy keeps trying to move him into this or that

episcopal position – wherever he goes there are those who don’t want him there,

and are prepared, sometimes, to be quite nastily vocal about it in the

simpering, passive-aggressive way that Anglicans do so well.

When his name was mooted as Bishop of Whitby, a number of

churchgoers (especially in the Archdeaconry of Cleveland) protested that their

previous two bishops had been opponents of the ordination of women as priests,

and now they wanted someone of a different view; funnily enough, it was the

Archdeacon of Cleveland who was bumped up to that job. Now, after Fr North was

put forward for the bishopric of Sheffield, cries have been raised that he would

not be able to treat the female clergy of his diocese equally with the men,

although as far as I know there haven’t been any complaints of his behaviour

while at Burnley. It’s a slightly different sort of position, as Sheffield’s

bishop is a fully-charged-up diocesan rather than a suffragan or assistant bishop like Burnley, but others around the

country prove that it’s not impossible to manage the problems that arise. No,

the issue seems to be that he is who he is and, as his personal character is

impeccable, that he associates with people who are not – ‘fogeys’, ‘reactionaries’,

and the like. And so, for the second time, he’s done the decent thing and,

recognising that as Sheffield’s bishop he would not be the ‘focus of unity’ he

would want to be, he’s withdrawn.

A couple of years ago the Church of England came to a

compromise that would allow the legislation to permit the consecration of women

as bishops to go ahead while still, just about, accommodating the people who

disagreed. When Philip North was consecrated as Bishop of Burnley in 2015 it

was a demonstration of how this might work: Archbishop of York John Sentamu refrained

from laying hands on him, delegating that to the bishops of Chichester, Pontefract

and Beverley, all of whom oppose the ordination of women, but the prayer of

consecration itself was said by all the bishops present, including Abp Sentamu and Libby Lane, seconds after her own

consecration as the first woman bishop in the Church of England. Of course it

was all messy, incoherent and in a way ludicrous, but via such messes,

incoherencies and ludicrousnesses does God’s Church of England proceed and work

crap out, and always has done.

There are a lot of people in the Church who were hopping mad

at that. They want tidiness, coherence, and sense, and call it justice. They

want the trads forced to knuckle under. They don’t believe compromise is

possible or honest.

To an extent, I know what they mean. The trad Anglo-Catholic

position, which is that the grace of God operates like a sort of divine electrical

current in which all the wiring has to be right or it doesn’t work – and the

circuitry requires not just no women priests but no bishops who have ever ordained women as priests – is nuts. It really is. I remember having a

conversation with a lovely member of our congregation who was grappling with

what would happen when Marion our curate was made priest and he might turn up

on a Sunday to find her at the altar rather than me. I said I thought the fundamental

question was whether the Holy Spirit was at work in Marion’s ministry or not. ‘Well,

put it like that’, mused Fred, ‘and it’s absurd to think any different. Of

course the Holy Spirit is at work in what she does.’ For a while I copied Fred

in on the service rota so he knew when not to come to mass, but then one day he

came and took communion from Marion and there’s never been a problem since. I

never tackled him about it. The trad-Catholic position is so ridiculous that

what was done at Philip North’s consecration is very clearly in the manner of a

fig leaf to spare their embarrassment. One day they will have to face these

questions, as indeed they are, priest by priest, congregation by congregation.

There is no need to rub their noses in it.

But if Philip North can’t be a diocesan bishop because some

people in his prospective diocese are upset (and let’s say I would not be very surprised to discover that

Sheffield Cathedral had much to do with the protests), does this mean no trad-Catholic

can be, except, perhaps, in the diocese of Chichester? Surely ‘mutual

flourishing’ must mean that a woman can be Bishop of Chichester one day and an

opponent of women being ordained can be Bishop of Southwark (to pick a liberal

diocese)? If not, that hard-won agreement of 2015, and all the warm words said around

it, mean nothing at all.

Friday, 10 March 2017

Alma Mater

One of my treasured privileges is my Bodleian Library

reader’s card, issued when I was studying at Oxford and carefully guarded ever

since. Imagine my horror to discover a few weeks ago that I’d let it lapse! Once

upon a time, the greatest library in the world – though some other universities

might cavil at that title – guarded access to its collections jealously, and

once you lost your rights to get in, that was it, unless you could prove absolute,

incontestable academic need. Now, however, the new(ish) Bodley’s Librarian says

on the Library’s website that all Oxford alumni are ‘members of the Library’

and so I was emboldened to take a trip to the city yesterday to have lunch with

my friend Ms T and to attempt to renew my card.

Things change at the Bod., as in Oxford more generally, and yet they stay the same. A few

years ago, with the digitisation of the collection records, the great Catalogue

Room got rid of its ledger books. When I was an undergraduate, and for many

years after, this was the very hub of the Library, jammed full with people

heaving the great leather volumes, 18 inches long and four thick, onto the

desks in order to find the book or document they wanted, or impatiently waiting

until the relevant catalogue became free. On some pages you could see where the

little slips of paper bearing the book details had had to be peeled off and

moved around to make room for a new acquisition. The computer terminals are

infinitely more practical, but infinitely less picturesque. Yet of course the

room is still there; and so are some of the librarians. The volumes of the

English Place-Name Survey – one of my most regular stopping points – have been

moved, but, deliciously, their new location is on the shelves of Duke Humfrey’s

Library, the dark, oak-panelled section of the Bod. redolent with the scent of

wood and leather and, for contemporary visitors, shades of the Harry Potter films

in which it features.

The Admissions Office, where I had to go to renew my card,

is no longer in the Clarendon Building, but has moved across Broad Street to

what was the New Bod. – dating to 1934, and in Oxford things don’t get much newer

than that – and is now the Weston Library. Its glossy atrium, the Blackwell

Hall, is a splendid space, but the entrance to the refurbished reading rooms beyond is now via a 16th-century

stone gateway which used to stand at the way into the gardens of Ascott Park,

about ten miles away: it’s on loan from the Victoria & Albert Museum. Here

again the new is smoothed and rendered palatable with doses of the antique.

The blue of the sky features in my photographs of the day as

much as the buildings: conditions were perfect for photographing the city. I

found the little Victorian cottages where my ex Lady Arlen used to live,

although the rest of the Castle and Brewery quarter near them has been altered

quite radically. The church of St Thomas the Martyr is where my friend Comrade Tankengine the railway manager used to worship, though he would now have to

pick the few moments when the church is open. I had a shock when I saw the sign

‘History Faculty’ at a completely unexpected location until I remembered that

the Faculty had moved some years ago. The new building is, naturally, a very

old building.

I regarded the preposterous, Thatcherite, would-be-cool nineties

swagger of the Said Business School on my way from and back to the railway

station with the scorn I always feel for it.

Wednesday, 8 March 2017

Out and About

A couple of years ago I mentioned here my sense of triumph at having compiled a little 'pastoral directory' which would make my parish visiting so very much easier. It was a good idea, but keeping up with the information was a different matter and that I have failed to do. So I'm having another go.

One of the things I've tried to do in the past is to keep an eye on properties around the parish which change hands and, when the estate agent's sign comes down, to knock on the door and say hello to whoever happens to be in. I'm not sure how effective it is as an evangelical tactic (one couple I'd visited once came to the church to have their baby christened - not much of a result from all that time) but it does me good to have to speak to people who wouldn't normally come to church and it keeps me in touch a bit with what's happening in the community and the sort of people who are moving in.

So one of my jobs this week has been to re-start my lists from scratch and tour around the village looking for such properties. Firstly I notice that one of the big local estate agents must have been bought out because there is a new sign I keep seeing. But the bigger surprise is that there aren't many at all. There's one street in particular which I can usually rely on to be decorated with a rich variety of SOLD and LET signs, and yet on this sweep I found only one. The general paucity suggests that the housing market in this area is unusually sluggish and I wonder whether that portends anything more widely about the economy.

All clergy regard visiting as an important part of our duties, and all of us castigate ourselves for not doing more of it. The trouble is that the modern world makes it increasingly difficult as hardly anyone is at home any more and when they are the last thing they want is the priest knocking on the door. There's one elderly lady I've tried to visit at least four times and on each occasion I've popped 'Sorry you were out' notes through the letterbox. 'Thank you for your note', she says when we speak at church. Even hospital visiting is affected as people spend less and less time there. A member of our congregation had a heart attack a few days ago, was admitted to hospital on Friday afternoon and was back home again on Monday having had a minor operation in between. Once upon a time she'd have been laid up for a fortnight with that, but there was little sense me racing over to Frimley and interrupting her treatment when she was going to be home in a couple of days anyway.

One of the things I've tried to do in the past is to keep an eye on properties around the parish which change hands and, when the estate agent's sign comes down, to knock on the door and say hello to whoever happens to be in. I'm not sure how effective it is as an evangelical tactic (one couple I'd visited once came to the church to have their baby christened - not much of a result from all that time) but it does me good to have to speak to people who wouldn't normally come to church and it keeps me in touch a bit with what's happening in the community and the sort of people who are moving in.

So one of my jobs this week has been to re-start my lists from scratch and tour around the village looking for such properties. Firstly I notice that one of the big local estate agents must have been bought out because there is a new sign I keep seeing. But the bigger surprise is that there aren't many at all. There's one street in particular which I can usually rely on to be decorated with a rich variety of SOLD and LET signs, and yet on this sweep I found only one. The general paucity suggests that the housing market in this area is unusually sluggish and I wonder whether that portends anything more widely about the economy.

All clergy regard visiting as an important part of our duties, and all of us castigate ourselves for not doing more of it. The trouble is that the modern world makes it increasingly difficult as hardly anyone is at home any more and when they are the last thing they want is the priest knocking on the door. There's one elderly lady I've tried to visit at least four times and on each occasion I've popped 'Sorry you were out' notes through the letterbox. 'Thank you for your note', she says when we speak at church. Even hospital visiting is affected as people spend less and less time there. A member of our congregation had a heart attack a few days ago, was admitted to hospital on Friday afternoon and was back home again on Monday having had a minor operation in between. Once upon a time she'd have been laid up for a fortnight with that, but there was little sense me racing over to Frimley and interrupting her treatment when she was going to be home in a couple of days anyway.

Monday, 6 March 2017

Tumulus (2005)

There’s a well-known photograph of Polly Harvey showing her

standing in a room which is unremarkable at first glance but somehow slightly

threatening – made the more so by the large spider on a table in the

foreground, pooled in the light from a lamp. It’s from early on in her career –

it could be from 1991 and is certainly no later than 1992. She doesn’t look

quite as skinny as she became a bit after that. I knew that the photo had been

taken by a gentleman called John Miles, and that he’d used PJ as a model a few

years later as well: in one image (‘Man and Woman’) he dresses her in a floaty

white dress anticipating her White Chalk-era

outfits, and also in a man’s black suit which hangs off her, and has her hold

hands with herself in an otherworldly dance. I utilised another of the ‘spider’

photos when talking here about Polly’s first album, Dry: it must be John Miles’s, though you can’t find it attributed

anywhere.

It was only very recently that I looked at Mr Miles’s

website and discovered he was based in Dorset; I thought I might buy his book, Tumulus. I have to confess I gibbed a

bit at the price it would have taken to import it from the publisher in the US,

but found a second-hand copy on Abebooks, which turned out, when it arrived, to

be ex-library stock from Dorchester, rather a nice synchronicity. There’s an

independent film-maker called Sarah Miles a couple of whose productions PJH had

taken part in; she plays a dangerously thin bunny girl in one, and in another,

an inconclusive tale about two teenage Japanese girls who unaccountably find

themselves going to school in Lyme Regis, she’s what appears to be a white-draped

Japanese ghost. I’d speculated whether John Miles might be related to Sarah,

and so it turned out: he’s her father. I’d wondered whether Ms Miles had met Ms

Harvey at art college, but as she’s about ten years older that’s not very

likely. Again, although John Miles taught at Beaminster Secondary School where

Polly was a pupil, he’d left long before then, so that can’t be the connection,

either. In his description of how the ‘Spider’ photo came about, he merely says

that he planned to do it after his son gave him the spider in a case, and she

sort of turned up at the right time, which I don’t quite believe. He says

nothing at all in explanation of how David bloody Hockney is in one of the

other shots.

It’s a peculiar book, it turns out. In the title photo (one

of the ones Mr Miles is proudest of in his career, he says) a little girl looks

mischievously – sinisterly – off to the right, the eponymous burial mound

behind her, while on the left hand side is what seems to be a cupboard door

with a mirror reflecting two older figures, one of them a woman whose face is

obscured. There’s not much obvious Dorset material, though apparently the great

majority of the photos were taken close to Mr Miles’s base in Loders – one snap

of a wedding party shows Loders church, while another has a young girl framed

against the toothy ruins of Sherborne Old Castle, just poking over the grass

behind her head. The tumulus itself could be anywhere, really. A lot of the

photos are collages, compiled from multiple exposures; many have an

unsettlingly dark humour to them, and in most you have no idea what might be

going on. The Loders wedding is possibly the only one that’s pure reportage,

recording a fleeting moment in local life. Or is it? Having looked through the

others you become increasingly unsure of anything. Given that the images in

this collection were taken over a long while, you start to wonder whether this adult is the same as this child with the addition of 15 to 20

years. It’s a world recognisably our own, yet skewed and unfamiliar: morbid would not be an unreasonable

word. Mr Miles favours locations which increase the sense of breakdown in

normality, rubbish-strewn sheds, unkempt rooms, barns with holes in walls and

roofs – the Other Dorset, maybe, the world behind the mirror. Ms H seems at

home here.

In this interview with fellow photographer Robin Mills, John Miles describes how he set up the

Bettiscombe Press in the late 1960s with Michael Pinney, who he found ‘having a

firework party in my back garden’. Mr Pinney was the owner of Bettiscombe

Manor, home of the infamous Screaming Skull of Bettiscombe which is beloved of

every book on Dorset folklore you can cite. The Press was designed to ‘publish

work in the way the artist would like it to be published’ (a very Harveyan

sentiment) and produced a series of small-run books of poetry, photography and

art in the early 1970s, some of which you can pick up quite cheaply, while

others are a little more exclusive, prices edging towards £2 a page. I’m quite

intrigued by Michael Pinney’s own book, Clothes

in a Museum; his wife Betty’s elaborate doll’s house – a work of art in its

own right – is in the collection of the Bethnal Green Museum of Childhood.

Just as a final little aside, that interview with John Miles

appeared in the independent West Dorset magazine Marshwood Vale, another of whose contributors is Clive

Stafford-Smith – Shaker Aamer’s lawyer who also did a piece about the County

Hospital at Dorchester for PJH’s notorious edition of the Today programme in 2014. Dorset mafia ahoy.

Saturday, 4 March 2017

Sites of Memory

How can it be nearly a quarter of a century since I worked

in Wimborne? Of course I’m still there quite often, as my sister lives there,

but it’s been a while since I was in the Minster, a church which fascinated me

ever after we went on a trip to look round it, when I was in the last year of

primary school, I think. I remember making a cardboard model of it. It’s far

from obviously beautiful – though that east end with its three soaring windows

is a sight you won’t forget (despite the glass not being all that good) – but it

works on an intimate scale for such a big building. When I became a Christian,

if that’s what I was then, the Minster was where I went to worship, first only

at the Midnight Mass, then, gradually, more often.

Thursday this week was so sunny and bright I took the chance

to pop down to Dorset, to look for a holy well, and to see my mum who’s been

poorly. I decided to stop off briefly at the Minster on my way between

well-site and mum-site. In one of the side chapels I saw a new oak altar rail

and a little plaque on them, discreetly to one side: ‘In memory of Phyllis

Saville, 1908-1994’.

Phyl was a profoundly lovely lady. She was President of the

Museum Trust in Wimborne when I worked there, all those years ago, as well as

being involved in other charities too. Widowed many years then, she had an

optimism in her approach to life that put my early-twenties misery to shame.

She was tough but immensely warm and open to everything that was going on

around her, and a stalwart ally in my boss Stephen’s efforts to make the Museum

a more up-to-date and welcoming place. Her flat was bright and white with the

occasional cross or icon on the wall.

One Sunday morning Mass at the Minster was interrupted and

words were whispered to the Rector. He rushed to a nearby lane where Phyl was

dying. It transpired that she’d been stabbed by a disturbed teenager – she may

have found him damaging a wall and told him to stop – and her death quite

naturally shocked the small town. Stephen the curator looked ashen on the national news.

‘That’s really disturbing,’ said Ms Formerly Aldgate when I told her the story. Strangely, at the time it wasn’t. Of course it was

tragically sad, a brutal end to a life of quiet hopefulness and dedication in

so many different ways. But, whatever the national media made of the event (and

they tried their best to turn it into a you’re-not-safe-on-the-streets kind of

story), I never heard anyone locally drawing any broader conclusions from what

happened to Phyl. It was simply a horrible tragedy, and aroused neither anger

nor fear. Everyone seemed to accept that the boy who killed Phyl was a kind of

victim too. A prize for young musicians was set up in her memory, and there she

is, in the Minster, memorialised in the altar rails.

It always seemed to me as though the deeply Christian life

she had led had absorbed the pain and rage of that terrible act before it had

even happened, as though not even that could truly touch her. In my memory, at

least, the gentle radiance of this one old lady has never been extinguished by

the way her life came to an end. On the contrary, perhaps the way the town

reacted to her death was her last service to the world. Then again, maybe not

her very last service: perhaps she prays for Wimborne, even now.

Thursday, 2 March 2017

When I'm Burning Crosses

On Shrove Tuesday, the rest of the country may turn its mind

to pancakes, but if you are a clergyperson whose outlook is – I exaggerate for

effect – anywhere to the Catholic side of the late Dr Ian Paisley, you will be

looking forward to the licensed act of pyromania that is the burning of the

palm crosses. The intense, moving liturgy of Ash Wednesday requires, well, ash,

and though you can buy it pre-prepared from well-known ecclesiastical

wholesalers, it’s much more fun to make it yourself.

It was curate Marion’s turn to take the earlier of our two

Masses-with-Ashing. ‘Do I have to burn the crosses in front of everyone?’ she

asked nervously. Of course not, it takes ages! Apparently at her previous

church they had the custom of setting light to a single palm in the middle of

the service, and crushing it into a bowl of oil resulting in a dark liquid that

was then used to mark the congregation’s foreheads with the sign of the cross.

I would argue that this is not ash so much as gloop, and picturesque though it

may be this process is entirely unnecessary and open to all sorts of things

going wrong.

As, of course, is the more mainstream practice; it just

happens (usually) a safe distance from the church. Here, for a couple of weeks

before Lent begins, we gather up the blessed crosses from the previous year’s

Palm Sunday observances which, hopefully, people have kept at home in

sufficient numbers. I then take them home.

Over the years I have developed a system that works

tolerably well (others may do it differently). First, the palms need to be cut

up: in their ‘natural’ state they are folded and looped in such a way that the

thick bits are very hard to burn. The smaller the pieces, the better. Then,

they are put into a metal container (an old biscuit tin suffices); I’ve found

it helpful to add a bit of paraffin as an accelerant (though not too much).

This year I had an old purificator to get rid of so that was cut up and doused

with paraffin and the palm pieces laid on top of it.

The weather is another important consideration here. You

don’t want to do the burning in the house, because it produces a) a surprising

amount of heat and b) a lot of acrid smoke once the actual burning is over.

However a day that’s too breezy will cause you a lot of problems, more than if

it’s wet. I am lucky in that the area outside my back door is quite sheltered;

and this year conditions were almost ideal anyway.

So now the time has come to commit the act. I still hazard

my safety with matches but a long-handled lighter would be better. It’s helpful

to have something suitable (metal but with a non-metal yet non-meltable handle)

to stir the bits round with so that they all get consumed. As much ash should

be produced as possible because it doesn’t go very far, and you’d be surprised

at how little ash a pile of, say, fifty palm crosses resolves into. I usually

find that a couple of supplementary splashes of paraffin and lightings are

required to get rid of enough of the pieces.

Once all this is done and the ash has cooled down, it needs

to be broken up. If you’ve used a biscuit tin or something to burn the crosses

in, you can now pop in some suitably heavy and impervious object (a 50p piece

will do well), put the lid on and give it a good shake. You then need to sieve

the resulting ash to remove all the remaining big pieces and achieve the

necessary consistency; sometimes more than one sieving is needed, and you may

like to try to crush some of the residue to get the most possible use out of

it. As the ash has come from objects which have been blessed at some point,

whatever bits are left over I prefer to scatter in the garden rather than put

in the bin.

And there you have it: your ash for the year. Now, you may

well argue that just because this is good Dangerous Book for Boys-type fun for

clergy it doesn’t justify all the time you spend doing it. But there is an

elemental circularity about reusing the crosses from last year – the same

people bring them back who are then marked with their ashes, their dead

remains, to express their own mortal nature. We are mortal, formed of the dust

of the earth: yet God stoops to the measure of our lowliness, touches us,

releases us from what we are. The cross is the sign of death and the sign of

life at once. It wouldn’t be the same buying the ash from elsewhere.

So we knelt on Ash Wednesday evening, first me, and then

Julie the sacristan who marked me, then everyone else in turn: an ecumenical

gathering, a couple of Roman Catholics, a Baptist minister, a smattering of

evangelical Anglicans as well as the Swanvale Halt folk. Those unspeakably deep

words, that resonate with the whole story of who we are, we humans: Remember

that you are dust, and to dust you shall return: repent, and believe in the

Gospel.